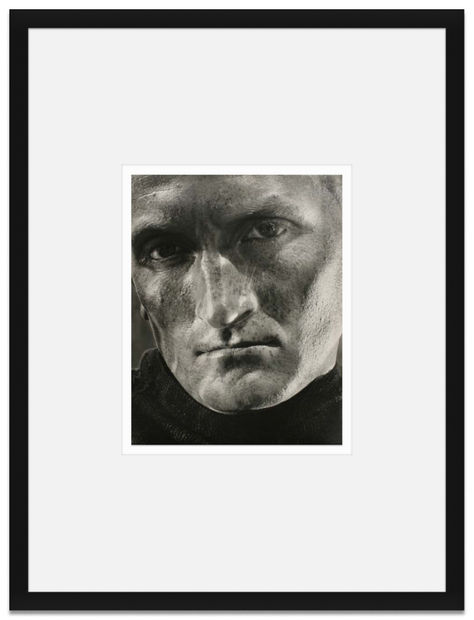

Helmar Lerski 1871, Strasbourg, France-1956, Zürich, Switzerland

-

Helmar Lerski. Self-portrait

Helmar Lerski. Self-portrait -

Helmar Lerski occupies a singular position in twentieth-century photography. For him, light was not merely a technical condition but the central instrument of artistic construction.

“Light is proof that a photographer can create freely, following his mind’s eye, like a painter, designer, or sculptor,” he wrote—an assertion that succinctly defines his approach. Illumination in Lerski’s work functions as structure, contour, and narrative force.

After more than two decades as an actor in the United States, Lerski turned to photography, later moving fluidly between still image and cinema. His theatrical background proved formative. Drawing upon stage lighting techniques, he approached portraiture as a spatial and dramatic composition rather than a neutral record. Light became a sculptural medium capable of reshaping the face and reorganizing perception.

By the 1910s and 1920s, Lerski had developed a highly distinctive portrait language. Rather than pursuing strict likeness or individual physiognomic detail, he sought to reveal archetypal presence. Through sharply contrasted illumination, he filtered out anecdotal elements and concentrated attention on structural form. Using mirrors and carefully directed beams, he produced dramatic modulations of shadow and highlight, transforming the human face into a sculpted topography—at times resembling relief or abstraction.

These effects were achieved without elaborate technical apparatus. Lerski relied on a large-format camera, mirrors, and contact prints. The innovation resided not in machinery but in conception: a rigorous redefinition of portraiture as a study of transformation. He regarded his principal breakthrough as the ability to demonstrate how shifts in camera angle and lighting could generate profound metamorphoses within a single face, revealing multiple psychological states through purely formal means.

Among his most consequential bodies of work is the series commonly known as Jewish Faces, initiated after his travels to Palestine beginning in 1931. These portraits combined expressive intensity with formal experimentation and quickly provoked ideological, national, and religious debate. Lerski conceived the project as an exploration of collective identity through typology. As he stated: “I want to show only the prototype in all its off-shoots… so intensely that the prototype is recognizable in all later branches.”

The series later expanded to include Arabic Faces and Working Hands, broadening its anthropological and social scope. Exhibited at the Tel Aviv Museum of Art in 1945, these works underscored Lerski’s ambition to construct a visual archive shaped as much by light and form as by historical circumstance.

Lerski’s engagement with cinema further extended his formal investigations. His films, including Avodah and Adamah, are marked by rhythmic editing, dynamic composition, and a strong graphic sensibility. Contemporary critics drew parallels between his cinematic language and the montage experiments of Sergei Eisenstein as well as the visual orchestration of Leni Riefenstahl. Across media, his practice maintained a consistent emphasis on structure, light, and the expressive capacity of the human figure.

Today, Helmar Lerski is regarded as a major innovator of twentieth-century photography. Alongside figures such as Alfred Stieglitz and Edward Steichen, he is recognized for redefining the possibilities of photographic portraiture and for advancing a modernist understanding of light as a generative artistic force.

Works by Helmar Lerski have been exhibited and are held in major institutions, including:

Tel Aviv Museum of Art, Tel Aviv

Museum of Modern Art, New York

Israel Museum, Jerusalem

Musée d'Art et d'Histoire du Judaïsme, Paris

Albertina, Vienna

Currier Museum of Art, Manchester, NH

Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

-

Works

-

'Der Mensch – Mein Bruder'

-

‘Der Mensch – Mein Bruder’ (Mankind. My Brother), 1958

-

Lerski Pictures (1911–1914)

-

-

Everyday Faces (1928–1931)

-

-

Arabs and Jews (1931–1935)

-

-

In his frequent correspondence with Albert Einstein, Lerski reflected on the state of the Jewish community. Einstein, aware of Lerski’s idea as early as 1930, wrote to him: “The Jews today are more a national than a religious community. The documentation of this type, as difficult as it may be, thus fulfills an active wish.”

In 1932, Lerski settled in Tel Aviv, where he remained until his return to Europe in 1948. He continued his portraiture work, expanding his concept for Jewish portraits to include the series “Palestinian Portraits” and “Arab Portraits.”

-

Metamorphosis Through Light (1936)

-

-

Hands Portraits (1944)

-

-

-

Viewing Rooms